This article aims to outline all of the key points of the Python programming language. My target is to keep the information short, relevant, and focus on the most important topics which are absolutely required to be understood.

After reading this blog, you will be able to use any Python library or implement your own Python packages.

You are not expected to have any prior programming knowledge and it will be very quick to grasp all of the required concepts.

I will also highlight top discussion questions that people usually query regarding Python programming language.

Lets build the knowledge gradually and by the end of the article, you will have a thorough understanding of Python.

This article contains 25 key topics. Let’s Start.

1. Introducing Python

What Is Python?

- Interpreted high-level object-oriented dynamically-typed scripting language.

- As a result, run time errors are usually encountered.

Why Python?

- Python is the most popular language due to the fact that it’s easier to code and understand it.

- Python is an object-oriented programming language and can be used to write functional code too.

- It is a suitable language that bridges the gaps between business and developers.

- Subsequently, it takes less time to bring a Python program to market compared to other languages such as C#/Java.

- Additionally, there are a large number of python machine learning and analytical packages.

- A large number of communities and books are available to support Python developers.

- Nearly all types of applications, ranging from forecasting analytical to UI, can be implemented in Python.

- There is no need to declare variable types. Thus it is quicker to implement a Python application.

Why Not Python?

- Python is slower than C++, C#, Java. This is due to the lack of Just In Time optimisers in Python.

- Python syntactical white-space constraint makes it slightly difficult to implement for new coders.

- Python does not offer advanced statistical features as R does.

- Python is not suitable for low-level systems and hardware interaction.

How Does Python Work?

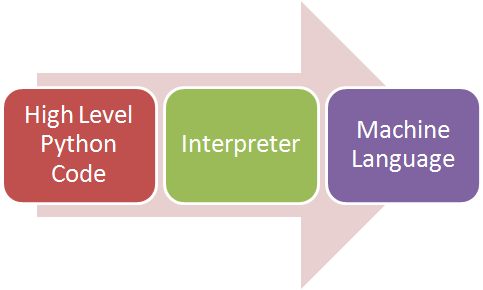

This image illustrates how python runs on our machines:

The key here is the Interpreter that is responsible for translating high-level Python language to low-level machine language.

The way Python works is as follows:

- A Python virtual machine is created where the packages (libraries) are installed. Think of a virtual machine as a container.

- The python code is then written in .py files

- CPython compiles the Python code to bytecode. This bytecode is for the Python virtual machine.

Now, this virtual machine is machine-dependent but the Python code isn’t.

4. When you want to execute the bytecode then the code will be interpreted at runtime. The code will then be translated from the bytecode into the machine code. The bytecode is not dependent on the machine on which you are running the code. This makes Python machine-independent.

Python byte code is Python virtual machine-dependent and this makes Python machine-independent.

The point to note is that we can write Python code in one OS, copy it to another OS and simply run it.

2. Variables — Object Types And Scope

- Variables store information that can be used and/or changed in your program. This information can be an integer, text, collection, etc.

- Variables are used to hold user inputs, local states of your program, etc.

- Variables have a name so that they can be referenced in the code.

- The fundamental concept to understand is that everything is an object in Python.

Python supports numbers, strings, sets, lists, tuples, and dictionaries. These are the standard data types. I will explain each of them in detail.

Declare And Assign Value To Variable

Assignment sets a value to a variable.

To assign variable a value, use the equals sign (=)

myFirstVariable = 1

mySecondVariable = 2

myFirstVariable = "Hello You"- Assigning a value is known as binding in Python. In the example above, we have assigned the value of 1 to myFirstVariable.

Note how I assigned an integer value of 1 and then a string value of “Hello You” to the same myFirstVariable variable. This is possible due to the fact that the data types are dynamically typed in python.

This is why Python is known as a dynamically typed programming language.

If you want to assign the same value to more than one variables then you can use the chained assignment:

myFirstVariable = mySecondVariable = 1Numeric

- Integers, decimals, floats are supported.

value = 1 #integer

value = 1.2 #float with a floating point- Longs are also supported. They have a suffix of L e.g. 9999999999999L

Strings

- Textual information. Strings are sequence of letters.

- A string is an array of characters

- A string value is enclosed in quotation marks: single, double or triple quotes.

name = 'farhad'

name = "farhad"

name = """farhad"""- Strings are immutable. Once they are created, they cannot be changed e.g.

a = 'me' #Updating it will fail:

a[1]='y' #It will throw a Type Error- When string variables are assigned a new value then internally, Python creates a new object to store the value.

Therefore a reference/pointer to an object is created. This pointer is then assigned to the variable and as a result, the variable can be used.

We can also assign one variable to another variable. All it does is that a new pointer is created which points to the same object:

a = 1 #new object is created and 1 is stored there, new pointer is created, the pointer connects a to 1

b = a #new object is not created, new pointer is created that connects b to 1Variables can have local or global scope.

Local Scope

- Variables declared within a function, as an example, can only exist within the block.

- Once the block exists, the variables also become inaccessible.

def some_funcion():

TestMode = False

print(TestMode) <- Breaks as the variable doesn't exist outsideIn Python, if-else and for/while loop block doesn’t create any local scope.

for i in range(1, 11):

test_scope = "variable inside for loop"

print(test_scope)Output:

variable inside for loop

With if-else block

is_python_awesome = True

if is_python_awesome:

test_scope = "Python is awesome"

print(test_scope)Output:

Python is awesome

Global Scope

- Variables that can be accessed from any function have a global scope. They exist in the __main__ frame.

- You can declare a global variable outside of functions. It’s important to note that to assign a global variable a new value, you will have to use the “global” keyword:

TestMode = True

def some_function():

global TestMode

TestMode = False

some_function()

print(TestMode) <--Returns FalseRemoving the line “global TestMode” will only set the variable to False within the some_function() function.

Note: Although I will write more on the concept of modules later, but if you want to share a global variable across a number of modules then you can create a shared module file e.g. configuration.py and locate your variable there. Finally, import the shared module in your consumer modules.

Finding Variable Type

- If you want to find the type of a variable, you can implement:

type('farhad')

--> Returns <type 'str'>Comma In Integer Variables

- Commas are treated as a sequence of variables e.g.

9,8,7 are three numeric variables

3. Operations

- Allows us to perform computation on variables

Numeric Operations

- Python supports basic *, /, +, –

- Python also supports floor division

1//3 #returns 0

1/3 #returns 0.333 - Note: the return type of division is always float as shown below:

a = 10/5

print(type(a)) #prints float- Additionally, python supports exponentiation via ** operator:

2**3 = 2 * 2 * 2 = 8- Python supports Modulus (remainder) operator too:

7%2 = 1There is also a divmod in-built method. It returns the divider and modulus:

print(divmod(10,3)) #it will print 3 and 1 as 3*3 = 9 +1 = 10String Operations

Concat Strings:

'A' + 'B' = 'AB'Remember string is an immutable data type, therefore, concatenating strings creates a new string object.

Repeat String:

'A'*3 #will repeat A three times: AAASlicing:

y = 'Abc'

y[:2] = ab

y[1:] = bc

y[:-2] = a

y[-2:] = bcReversing:

x = 'abc'

x = x[::-1]Negative Index:

If you want to start from the last character then use negative index.

y = 'abc'

print(y[:-1]) # will return abIt is also used to remove any new line carriages/spaces.

Each element in an array gets two indexes:

- From left to right, the index starts at 0 and increments by 1

- From right to left, the index starts at -1 and decrements by 1

- Therefore, if we do y[0] and y[-len(y)] then both will return the same value: ‘a’

y = 'abc'

print(y[0])

print(y[-len(y)])Finding Index

name = 'farhad'

index = name.find('r') #returns 2name = 'farhad'

index = name.find('a', 2) # finds index of second a#returns 4For Regex, use:

- split(): splits a string into a list via regex

- sub(): replaces matched string via regex

- subn(): replaces matched string via regex and returns number of replacements

Casting

- str(x): To string

- int(x): To integer

- float(x): To floats

Set Operations

- A set is an unordered data collection without any duplicates. We can define a set variable as:

set = {9,1,-1,5,2,8,3, 8}

print(set)This will print: {1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, -1}

Note duplicates are removed.

Set has a item in set, len(set) and for item in set operations. However it does not support indexing, slicing like lists.

Some of the most important set operations are:

- set.add(item) — adds item to the set

- set.remove(item) — removes item from the set and raises error if it is not present

- set.discard(item) — removes item from the set if it is present

- set.pop() — returns any item from the set, raises KeyError if the set is empty

- set.clear() clears the set

Intersect Sets

- To get what’s common in two sets

a = {1,2,3}

b = {3,4,5}

c = a.intersection(b)Difference In Sets

- To retrieve the difference between two sets:

a = {1,2,3}

b = {3,4,5}

c = a.difference(b)Union Of Collections

- To get a distinct combined set of two sets

a = {1,2,3}

b = {3,4,5}

c = a.union(b)Ternary Operator

- Used to write conditional statements in a single line.

Syntax:

[If True] if [Expression] Else [If False]

For example:

Received = True if x == 'Yes' else False4. Comments

Single Line Comments

# This is a single line commentMultiple Line Comments

One can use:

```this is a multi

line

comment```5. Expressions

Expressions can perform boolean operations such as:

- Equality: ==

- Not Equal: !=

- Greater: >

- Less: <

- Greater Or Equal >=

- Less Or Equal <=

6. Pickling

Converting an object into a string and dumping the string into a binary file is known as pickling. The reverse is known as unpickling.

7. Functions

- Functions are sequence of statements that you can execute in your code. If you see repetition in your code then create a reusable function and use it in your program.

- Functions can also reference other functions.

- Functions eliminate repetition in your code. They make it easier to debug and find issues.

- Finally, functions enable code to be understandable and easier to manage.

- In short, functions allow us to split a large application into smaller chunks.

Define New Function

def my_new_function():

print('this is my new function')Calling Function

my_new_function()Finding Length Of String

Call the len(x) function

len('hello') # prints 5Arguments

- Arguments can be added to a function to make the functions generic.

- This exercise is known as generalization.

- You can pass in variables to a method:

def my_new_function(my_value):

print('this is my new function with ' + my_value)

- Optional arguments:

We can pass in optional arguments by providing a default value to an argument:

def my_new_function(my_value='hello'):

print(my_value)#Calling

my_new_function() => prints hello

my_new_function('test') => prints test

- *arguments:

If your function can take in any number of arguments then add a * in front of the parameter name:

def myfunc(*arguments):

return amyfunc(a)

myfunc(a,b)

myfunc(a,b,c)

- **arguments:

It allows you to pass a varying number of keyword arguments to a function.

You can also pass in dictionary values as keyword arguments.

def test(*args, **kargs):

print(args)

print(kargs)

print(args[0])

print(kargs.get('a'))

alpha = 'alpha'

beta = 'beta'

test(alpha, beta, a=1, b=2)

This will print:

(3, 1)

(‘alpha’, ‘beta’)

{‘a’: 1, ‘b’: 2}

alpha

1

Return

- Functions can return values such as:

def my_function(input):

return input + 2

- If a function is required to return multiple values then it’s suitable to return a tuple (comma separated values). I will explain tuples later on:

resultA, resultB = get_result()get_result() can return ('a', 1) which is a tuple

Lambda

- Single expression anonymous function.

- It is an inline function.

my_lambda = lambda x,y,z : x - 100 + y - zmy_lambda(100, 100, 100) # returns 0

Syntax:

variable = lambda arguments: expression

Lambda functions can be passed as arguments to other functions.

Object Identity

I will attempt to explain the important subject of Object Identity now.

Whenever we create an object in Python such as a variable, function, etc, the underlying Python interpreter creates a number that uniquely identifies that object. Some of the objects are created up-front.

When an object is not referenced anymore in the code then it is removed and its identity number can be used by other variables.

dir() and help()

- dir() -displays defined symbols

- help() — displays documentation

Let’s understand it in detail:

Consider the code below:

var_one = 123

def func_one(var_one):

var_one = 234

var_three = 'abc'var_two = 456

print(dir())

var_one and var_two are the two variables that are defined in the code above. Along with the variables, a function named func_one is also defined. An important note to keep in mind is that everything is an object in Python, including a function.

Within the function, we have assigned the value of 234 to var_one and created a new variable named var_three and assigned it a value of ‘abc’.

Now, let’s understand the code with the help of dir() and id()

The above code and its variables and functions will be loaded in the Global frame. The global frame will hold all of the objects that the other frames require. As an example, there are many built-in methods loaded in Python that are available to all of the frames. These are the function frames.

Running the above code will print:

[‘__annotations__’, ‘__builtins__’, ‘__cached__’, ‘__doc__’, ‘__file__’, ‘__loader__’, ‘__name__’, ‘__package__’, ‘__spec__’, ‘func_one’, ‘var_one’, ‘var_two’]

The variables that are prefixed with __ are known as the special variables.

Notice that the var_three is not available yet. Let’s execute func_one(var_one) and then assess the dir():

var_one = 123

def func_one(var_one):

var_one = 234

var_three = 'abc'

var_two = 456

func_one(var_one)

print(dir())

We will again see the same list:

['__annotations__', '__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'func_one', 'var_one', 'var_two']

This means that the variables within the func_one are only within the func_one. When func_one is executed then a Frame is created. Python is top-down therefore it always executes the lines from top to the bottom.

The function frame can reference the variables in the global frame but any other function frame cannot reference the same variables that are created within itself. As an instance, if I create a new function func_two that tries to print var_three then it will fail:

var_one = 123

def func_one(var_one):

var_one = 234

var_three = 'abc'

var_two = 456

def func_two():

print(var_three)

func_one(var_one)

func_two()

print(dir())

We get an error that NameError: name ‘var_three’ is not defined

What if we create a new variable inside func_two() and then print the dir()?

var_one = 123

def func_one(var_one):

var_one = 234

var_three = 'abc'

var_two = 456

def func_two():

var_four = 123

print(dir())func_two()

This will print var_four as it is local to func_two.

How does Assignment work In Python?

This is by far one of the most important concepts to understand in Python. Python has an id() function.

When an object (function, variable, etc.) is created, CPython allocates it an address in memory. The id() function returns the “identity” of an object. It is essentially a unique integer.

As an instance, let’s create four variables and assign them values:

variable1 = 1

variable2 = "abc"

variable3 = (1,2)

variable4 = ['a',1]#Print their Ids

print('Variable1: ', id(variable1))

print('Variable2: ', id(variable2))

print('Variable3: ', id(variable3))

print('Variable4: ', id(variable4))

The ids will be printed as follows:

Variable1: 1747938368

Variable2: 152386423976

Variable3: 152382712136

Variable4: 152382633160

Each variable has been assigned a new integer value.

The first assumption is that whenever we use the assignment “=” then Python creates a new memory address to store the variable. Is it 100% true, not really!

I am going to create two variables and assign them to the existing variables.

variable5 = variable1

variable6 = variable4

print('Variable1: ', id(variable1))

print('Variable4: ', id(variable4))

print('Variable5: ', id(variable5))

print('Variable6: ', id(variable6))

Python printed:

Variable1: 1747938368

Variable4: 819035469000

Variable5: 1747938368

Variable6: 819035469000

Notice that Python did not create new memory addresses for the two variables. This time, it pointed both of the variables to the same memory location.

Let’s set a new value to the variable1. Remember 2 is an integer and integer is an immutable data type.

print('Variable1: ', id(variable1))

variable1 = 2

print('Variable1: ', id(variable1))

This will print:

Variable1: 1747938368

Variable1: 1747938400

It means whenever we use the = and assign a new value to a variable that is not a variable then internally a new memory address is created to store the variable. Let’s see if it holds!

What happens when the value is a mutable data type?

variable6 is a list. Let’s append an item to it and print its memory address:

print('Variable6: ', id(variable6))

variable6.append('new')

print('Variable6: ', id(variable6))

Note that the memory address remained the same for the variable as it is a mutable data type and we simply updated its elements.

Variable6: 678181106888

Variable6: 678181106888

Let’s create a function and pass a variable to it. If we set the value of the variable inside the function, what will it do internally? let’s assess

def update_variable(variable_to_update):

print(id(variable_to_update))

update_variable(variable6)

print('Variable6: ', id(variable6))

We get:

678181106888

Variable6: 678181106888

Notice that the id of variable_to_update points to the id of the variable 6.

This means that if we update the variable_to_update in a function and if variable_to_update is a mutable data type then we’ll update variable6.

variable6 = ['new']

print('Variable6: ', variable6)

def update_variable(variable_to_update):

variable_to_update.append('inside')update_variable(variable6)

print('Variable6: ', variable6)

This printed:

Variable6: [‘new’]

Variable6: [‘new’, ‘inside’]

It shows us that the same object is updated within the function as it was expected by both having the same ID.

If we assign a new value to a variable, regardless of if it’s immutable and mutable data type then the change will be lost once we come out of the function:

print('Variable6: ', variable6)

def update_variable(variable_to_update):

print(id(variable_to_update))

variable_to_update = ['inside']update_variable(variable6)

print('Variable6: ', variable6)

Variable6: [‘new’]

344115201992

Variable6: [‘new’]

Now an interesting scenario: Python doesn’t always create a new memory address for all new variables.

Finally, what if we assign two different variables a string value such as ‘a’. Will it create two memory addresses?

variable_nine = "a"

variable_ten = "a"

print('Variable9: ', id(variable_nine))

print('Variable10: ', id(variable_ten))

Notice, both the variables have the same memory location:

Variable9: 792473698064

Variable10: 792473698064

What if we create two different variables and assign them a long string value:

variable_nine = "a"*21

variable_ten = "a"*21

print('Variable9: ', id(variable_nine))

print('Variable10: ', id(variable_ten))

This time Python created two memory locations for the two variables:

Variable9: 541949933872

Variable10: 541949933944

This is because Python creates an internal cache of values when it starts up. This is done to provide faster results. It creates a handful of memory addresses for small integers such as between -5 to 256 and smaller string values. This is the reason why both of the variables in our example had the same ID.

== vs is

Sometimes we want to check whether two objects are equal.

- If we use == then it will check whether the two arguments contain the same data

- If we use is then Python will check whether the two objects refer to the same object. The id() needs to be the same for both of the objects

var1 = "a"*30

var2 = "a"*30

print('var1: ', id(var1)) #318966315648

print('var2: ', id(var2)) #168966317364

print('== :', var1 == var2) #returns True

print('is :', var1 is var2) #returns False

8. Modules

What is a module?

- Python is shipped with over 200 standard modules.

- A module is a component that groups similar functionality of your python solution.

- Any python code file can be packaged as a module and then it can be imported.

- Modules encourage componentised design in your solution.

- They provide the concept of namespaces to help you share data and services.

- Modules encourage code reusability and reduce variable name clashes.

PYTHONPATH

- This environment variable indicates where the Python interpreter needs to navigate to locate the modules. PYTHONHOME is an alternative module search path.

How To Import Modules?

- If you have a file: MyFirstPythonFile.py and it contains multiple functions, variables and objects then you can import the functionality into another class by simply doing:

import MyFirstPythonFile

- Internally, python runtime will compile the module’s file to bytes and then it will run the module code.

- If you want to import everything in a module, you can do:

import my_module

- If your module contains a function or object named my_object then you will have to do:

print(my_module.my_object)

Note: If you do not want the interpreter to execute the module when it is loaded then you can check whether the __name__ == ‘__main__’

2. From

- If you only want to access an object or parts of a module from a module then you can implement:

from my_module import my_object

- This will enable you to access your object without referencing your module:

print(my_object)

- We can also do from * to import all objects

from my_module import *

Note: Modules are only imported on the first import.

- If you want to use a Python module in C:

Use PyImport_ImportModule(module_name)

Namespace — two modules with same object name:

Use import over from if we want to use the same name defined in two different modules.

9. Packages

- Package is a directory of modules.

- If your Python solution offers a large set of functionalities that are grouped into module files then you can create a package out of your modules to better distribute and manage your modules.

- Packages enable us to organise our modules better which helps us in resolving issues and finding modules easier.

- Third-party packages can be imported into your code such as pandas/sci-kit learn and tensor flow to name a few.

- A package can contain a large number of modules.

- If our solution offers similar functionality then we can group the modules into a package:

from packageroot.packagefolder.mod import my_object

- In the example above, packageroot is the root folder. packagefolder is the subfolder under packageroot. my_module is a module python file in the packagefolder folder.

- Additionally, the name of the folder can serve as the namespace e.g.

from data_service.database_data_service.microsoft_sql.mod

Note: Ensure each directory within your package import contains a file __init__.py.

Feel free to leave the files blank. As __init__.py files are imported before the modules are imported, you can add custom logic such as start service status checks or to open database connections, etc.

PIP

- PIP is a Python package manager.

- Use PIP to download packages:

pip install package_name

10. Conditions

- To write if then else:

if a == b:

print 'a is b'

elif a < b:

print 'a is less than b'

elif a > b:

print 'a is greater than b'

else:

print 'a is different'

Note how colons and indentations are used to express the conditional logic.

Checking Types

if not isinstance(input, int):

print 'Expected int'

return None

You can also add conditional logic in the else part. This is known as nested condition.

#let's write conditions within else

else:

if a == 2:

print 'within if of else'

else:

print 'within else of else'

11. Loops

While

- Provide a condition and run the loop until the condition is met:

while (input < 0):

do_something(input)

input = input-1

For

- Loop for a number of times

for i in range(0,10)

- Loop over items or characters of a string

for letter in 'hello'

print letter

One-Liner For

Syntax:

[Variable] AggregateFunction([Value] for [item] in [collection])

Yielding

- Let’s assume your list contains a trillion records and you are required to count the number of even numbers from the list. It will not be optimum to load the entire list in the memory. You can instead yield each item from the list.

range(start, stop, step):

Generates numerical values that start at start, stop at stop with the provided steps. As an instance, to generate odd numbers from 1 to 9, do:

rint(list(range(1,10,2)))

Combine For with If

- Let’s do a simple exercise to find if a character is in two words

name = 'onename'

anothername = 'onenameonename'for character in name:

if character in anothername

print character

Break

- If you want to end the loop

for i in range(0,10):

if (i==5):

break

while True:

x = get_value()

if (x==1):

break

- Let’s write Fibonacci for loop:

def fib(input):

if (input <=1):

return(str(input))

else:

first = 0

second = 1

count = 0

for count in range(input):

result = first + second

print(first)

first = second

second = result

count = count+1#print statement will output the correct fib value

fib(7)

12. Recursion

- A function calling itself is known as recursion.

Let’s implement a factorial recursive function:

Rules:

- 0! = 1 #Factorial of 0 is 1

- n! = n(n-1)! #Factorial of n is n * factorial of n-1

Steps:

- Create a function called factorial with input n

- If n = 0 return 1 else do n x factorial of n-1

def factorial(n):

if n==0:

return 1

else:

return n * factorial(n-1)

Another Example: Let’s write Fibonacci recursive function:

Rules:

- First two digits are 0 and 1

- Rest add last two digits

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8…

Steps:

- Create a function called fibonacci that takes in an input n

- Create two variables first and second and assign them with values 0 and 1

- if n =0 return 0, if n = 1 return 1 else return (n-1) + (n-2)

def fibonacci(n):

if (n<=1):

return n

else:

return fibonacci(n-1)+fibonacci(n-2)print(fibonacci(6))

It is important to have an exit check otherwise the function will end up in an infinite loop.

13. Frames And Call Stack

- Python code is loaded into frames that are located into a Stack.

- Functions are loaded in a frame along with the parameters and variables.

- Subsequently, frames are loaded into a stack in the right order of execution.

- Stack outlines the execution of functions. Variables that are declared outside of functions are stored in __main__

- Stacks executes the last frame first.

You can use traceback to find the list of functions if an error is encountered.

14. Collections

Lists

- Lists are data structures that can hold a sequence of values of any data types. They are mutable (update-able).

- Lists are indexed by integers.

- To create a list, use square brackets:

my_list = ['A', 'B']

- To add/update/delete an item, use index:

my_list.append('C') #adds at the end

my_list[1] = 'D' #update

my_list.pop(1) # removes

or

del my_list[1:2] # removes

my_list.extend(another_list) # adds second list at end

- Addition, repetition and slices can be applied to lists (just like strings).

- List also supports sorting:

my_list.sort() #this is inplace sort

Note on pop():

- Pop from the end is O(1)

- Pop from start (

.pop(0)) is O(N) : all the elements inlist[1:]are physically moved one position to the left.

If you need to delete index position 0 frequently, use collections.deque.

Tuples

- Tuples are like lists in the sense that they can store a sequence of objects. The objects, again, can be of any type.

- Tuples are faster than lists.

- These collections are indexed by integers.

- Tuples are immutable (non-update-able)

my_tuple = tuple()

or

my_tuple = 'f','m'

or

my_tuple = ('f', 'm')

Note: If a tuple contains a list of items then we can modify the list. Also if you assign a value to an object and you store the object in a list and then change the object then the object within the list will get updated.

Dictionaries

- Dictionary is one of the most important data structure in the programming world. It stores key/value pair objects.

- It has many benefits e.g. optimised data retrieval functionality.

my_dictionary = dict()

my_dictionary['my_key'] = 1

my_dictionary['another_key'] = 2

- You can also create a dictionary as:

my_dictionary = {'my_key':1, 'another_key':2}

- Print dictionary contents

for key in dictionary:

print key, dictionary[key]

- Values of a dictionary can be of any type including strings, numerical, boolean, lists or even dictionaries.

dictionary.items() # returns items#checking if a key exists in a dictionary

if ('some key' in dictionary):

#do something

Few of the important functions:

get(key, default): returns value for key else returns default

pop(key, default): returns value for key and deletes the item with key else returns default

popitem(): removes random item from the dictionarydictionary1.update(dictionary2): merges two dictionaries

Note: If you want to perform vectorised/matrix operations on a list then use NumPy Python package

15. Compilation And Linking

- These features can be utilised to use a file that is written in another language e.g. C or C++ etc, as long as it is supported by the compiler.

- Once the code is written into a file then the file can be placed in the Modules directory of the distribution.

- It is important to add a line in the Setup.local file to ensure that the newly created file can be loaded. Run the file using spam file.o

- Changing the file requires running rebuildMakefile

Compilation:

- Allows compilation of new extensions without any error

Linking:

- Once the extensions are compiled, they can be linked.

16. Iterators

Iterators

- Allow traversing through a collection

- All iterators contain __iter__() and __next__() functions

- Simply execute iter(x) on lists, dictionaries, strings or sets.

- Therefore we can execute next(iter) where iter = iter(list) as an instance.

- Iterators are useful if we have a large number of items in a collection and we do not intend to load all of the files in memory at once. Iterators are memory efficient and can represent an infinite stream.

- There are common iterators which enable developers to implement functional programming language paradigm:

Filter

- Filter out values based on a condition

Map

- Applies a computation on each value of a collection. It maps one value to another value e.g. Convert Text To Integers

Reduce

- Reduces a collection of values to one single value (or a smaller collection) e.g. the sum of a collection. It can be iterative in nature.

Zip

- Takes multiple collections and returns a new collection.

- The new collection contains items where each item contains one element from each input collection.

- It allows us to transverse multiple collections at the same time

name = 'farhad'

suffix = [1,2,3,4,5,6]

zip(name, suffix)

--> returns (f,1),(a,2),(r,3),(h,4),(a,5),(d,6)

enumerate

enumerate can loop over an iterable and returns an automatic index for each of the elements:

for index, element in enumerate(iterator):

pass

Iterators require us to implement two key methods:

__iter__() and __next__()

Additionally, StopIteration needs to be raised when there are no values left to be returned.

We can make a function return an iterator by using a Generator. All we have to do is to use the yield keyword instead of return. The key is to yield one item at a time.

17. Object-Oriented Design — Classes

- Python allows us to create our custom types. These user-defined types are known as classes. The classes can have custom properties/attributes and functions.

- The object-oriented design allows programmers to define their business model as objects with their required properties and functions.

- A property can reference another object too.

- Python classes can reference other classes.

- Python supports encapsulation — instance functions and variables.

- Python supports inheritance.

class MyClass:

def MyClassFunction(self): #self = reference to the object

return 5#Create new instance of MyClass and then call the function

m = MyClass()

returned_value = m.MyClassFunction()

- An instance of a class is known as an object. The objects are mutable and their properties can be updated once the objects are created.

Note: If a tuple (immutable collection) contains a list (mutable collection) of items then we can modify the list. Also if you assign a value to an object and you store the object in a list and then change the object then the object within the list will get updated.

__init__

- __init__ function is present in all classes. It is executed when we are required to instantiate an object of a class. __init__ function can take any properties which we want to set:

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, first_property):

self.first_property = first_property def MyClassFunction(self):

return self.first_property

#Create an instance

m = MyClass(123)

r = m.MyClassFunction()r will be 123

Note: self parameter will contain the reference of the object, also referred to as “this” in other programming languages such as C#

__str__

- Returns stringified version of an object when we call “print”:

m = MyClass(123)

print m #Calls __str__

- Therefore, __str__ is executed when we execute print.

__cmp__

- Use the __cmp__ instance function if we want to provide custom logic to compare two objects of the same instance.

- It returns 1 (greater), -1 (lower) and 0 (equal) to indicate the equality of two objects.

- Think of __cmp__ like Equals() method in other programming language.

Overloading

- Methods of an object can be overloaded by providing more arguments as an instance.

- We can also overload an operator such as + by implementing our own implementation for __add__

Shallow Vs Deep Copy Of Objects

- Equivalent objects — Contains the same values

- Identical objects — Reference the same object — same address in memory

- If you want to copy an entire object then you can use the copy module

import copy

m = MyClass(123)

mm = copy.copy(m)

- This will result in shallow copy as the reference pointers of the properties will be copied.

- Therefore, if one of the properties of the object is an object reference then it will simply point to the same reference address as the original object.

- As a result, updating the property in the source object will result in updating the property in the target object.

- Therefore shallow copy copies reference pointers.

- Fortunately, we can utilise deep-copy:

import copy

m = MyClass(123)

mm = copy.deepcopy(m)

- If MyClass contains a property that references MyOtherClass object then the contents of the property will be copied in the newly created object via deepcopy.

- Therefore, deep copy makes a new reference of the object.

18. Object-Oriented Design — Inheritance

- Python supports the inheritance of objects. As a result, an object can inherit functions and properties of its parent.

- An inherited class can contain different logic in its functions.

- If you have a class: ParentClass and two subclasses: SubClass1, SubClass2 then you can use Python to create the classes as:

class ParentClass:

def my_function(self):

print 'I am here'

class SubClass1(ParentClass):

class SubClass2(ParentClass):

- Consequently, both subclasses will contain the function my_function().

- Inheritance can encourage code reusability and maintenance.

Note: Python supports multiple inheritances unlike C#

- Use Python’s abc module to ensure all subclasses contain the required features of the Abstract Base Class.

Multi-Inheritance:

class A(B,C): #A implments B and C

- If you want to call parent class function then you can do:

super(A, self).function_name()

There are a number of internal methods that we should be familiar with.

__str__(self): This function returns a user-friendly value to represent the object to the users.

__repr__(self): This function returns a developer-friendly value to represent the object to the users. If __str__() is missing then __repr()__ is called.

__eq__(self, other): This function can help us compute how to find if two objects are equal.

class Human:

def __init__(self, name, friends=[]):

self.name = name

self.friends = friends

def __str__(self):

return f'Name is: {self.name}'

def __repr__(self):

return 'Human({self.name}, {self.friends})'

def __eq__(self, other):

return self.name == other.name

human = Human('Farhad', ['Friend1', 'Friend2'])

print(human)

This will print: Name is: Farhad

If we remove __str__ function then it will call __repr__ instead:

This will print: Human(Farhad, [‘Friend1’, ‘Friend2’])

If we create two human instances with the same name and different friends then it will mark both of them as equal due to the __eq__ function:

human1 = Human('Farhad', ['Friend1', 'Friend2'])

human2 = Human('Farhad', ['ABC', 'DEF'])

print(human1 == human2) #prints True

19. Garbage Collection — Memory Management

- All of the objects in Python are stored in heap space. This space is accessible to the Python interpreter. It is private.

- Python has an in-built garbage collection mechanism.

- It means Python can allocate and de-allocate the memory for your program automatically such as in C++ or C#.

- Its responsibility is to clear the space in memory of those objects that are not referenced/used in the program.

As multiple objects can share memory references, python employs two mechanisms:

- Reference counting: Count the number of items an object is referenced, deallocate an object if its count is 0. The reference is incremented when the variable is assigned an object or when it is passed as an argument to any method.

- The second mechanism takes care of circular references, also known as cyclic references, by only de-allocating the objects where the allocation — deallocation number is greater than the threshold.

- New objects are created in Generation 0 in python. They can be inspected by:

import gc

collected_objects = gc.collect()

- Manual garbage collection can be performed on a timely or event-based mechanism.

- When a Python program exists then Python attempts to remove global objects and ones that have a circular reference.

20. I/O

From Keyboard

- Use the raw_input() function

user_says = raw_input()

print(user_says)

Files

- Use a with/as a statement to open and read a file. It is equivalent to the using statement in C#.

- with statement can take care of the closing of connections and other cleanup activities.

Open files

with open(file path, 'r') as my_file:

for line in my_file#File is closed due to with/as

Note: readline() can also be executed to read a line of a file.

To open two files

with open(file path) as my_file, open(another path) as second_file:

for (line number, (line1, line2)) in enumerate(zip(my_file, second_file):

Writing files

with open(file path, 'w') as my_file:

my_file.write('test')

Note: Use os and shutil modules for files.

Note: There are a large number of modes available, such as:

rw — read-write mode

r — read mode

rb — read in binary format mode e.g. pickle file

r+ — read for both reading and writing mode

a — append mode.

w+ — for reading and writing, overwrites if the file exists

SQL

Open a connection

import MySQLdb

database = MySQLdb.connect(“host”=”server”, “database-user”=”my username”, “password”=”my password”, “database-name”=”my database”)

cursor = database.cursor()

Execute a SQL statement

cursor.fetch("Select * From MyTable")

database.close()

Web Services

To query a rest service

import requests

url = 'http://myblog.com'

response = requests.get(url).text

To Serialise and Deserialise JSON

Deserialise:

import json

my_json = {"A":"1","B":"2"}

json_object = json.loads(my_json)

value_of_B = json_object["B"]

Serialise:

import json

a = "1"

json_a = json.dumps(a)

21. Error Handling

Raise Exceptions

- If you want to raise exceptions then use the raise keyword:

try:

raise TypError

except:

print('exception')

Catching Exceptions

- To catch exceptions, you can do:

try:

do_something()

except:

print('exception')

- If you want to catch specific exceptions then you can do:

try:

do_something()

except TypeError:

print('exception')

- If you want to use try/catch/finally then you can do:

try:

do_something()

except TypeError:

print('exception')

finally:

close_connections()

- finally part of the code is triggered regardless, you can use finally to close the connections to database/files, etc.

Try/Except/Else

try:

do something

except IfTryRaisedException1:

do something else

except (IfTryRaisedException2, IfTryRaisedException3)

if exception 2 or 3 is raised then do something

else:

no exceptions were raised

- else is executed when no exceptions have been raised.

- We can also assign exception to a variable by doing:

try:

do something

except Exception1 as my_exception:

do something about my_exception

- If you want to define user-defined constraints then use assert:

assert <bool>, 'error to throw'

Note: Python supports inheritance in exceptions

You can create your own exception class by:

class MyException(Exception): pass

22. Multi-Threading And GIL

- GIL is Global Interpreter Lock.

- It ensures that the threads can execute at any one time and allows CPU cycles to pick the required thread to be executed.

- GIL is passed onto the threads that are currently being executed.

- Python supports multi-threading.

Note: GIL adds overheads to the execution. Therefore, be sure that you want to run multiple threads.

23. Decorators

- Decorators can add functionality to code. They are essentially functions that call other objects/functions.

- Decorators are callable functions — therefore they return the object to be called later when the decorated function is invoked.

- Think of decorates that enable aspect-oriented programming

- We can wrap a class/function and then a specific code will be executed any time the function is called.

- We can implement generic logic to log, check for security checks, etc and then attribute the method with the @property tag.

- The most important concept to understand is that in Python, functions are objects. This means a function can return another function and one function can take another function as an argument. We can also define a function within another function. Functions can also be assigned to a variable.

Understanding decorators:

- Essentially a decorator is a function. It accepts another function as a parameter. It also returns a function. Let’s understand the steps:

- The decorator is a function that accepts a function as an input and returns an inner function:

def my_decorator(input): def my_inner_decorator(*args, **kwargs):

print('Hi FinTechExplained')

input(*args, **kwargs)

print('Bye FinTechExplained')

return my_inner_decorator

2. The input function is the one that the decorator is going to decorate.

3. The internal function is the function that performs the appropriate actions to the input function and then the decorator returns the inner function.

To use the decorator, use the @ sign:

@my_decorator

def print_num(number):

print('inside function:',number)print_num(1)The function printed:

Hi FinTechExplained

inside function: 1

Bye FinTechExplained

We can also pass other parameters to the decorator if required.

24. Unit Testing In Python

- There are a number of unit testing and mocking libraries available in Python.

- An example is to use unittest:

1.Assume your function simply decrements an input by 1

def my_function(input):

return input - 1

2. You can unit test it by:

import unittest

class TestClass(unittest.TestCase):

def my_test(self):

self.assertEqual(my_function(1), 0)) #checking 1 becomes 0

We can also use doctest to test code written in docstrings.

25. Top Python Discussion Questions

Why Should I Use Python?

- Simple to code and learn

- Object-oriented programming language

- Great Analytics and ML packages

- Faster to develop and bring my solution to market

- Offers in-built memory management facilities

- Huge community support and applications available

- No need to compile as it’s an interpreted language

- Dynamically typed — no need to declare variables

How To Make Python Run Fast?

- Python is a high-level language and is not suitable to access system-level programs or hardware.

- Additionally, it is not suitable for cross-platform applications.

- The fact that Python is a dynamically typed interpreted language makes it slower to be optimised and run when compared to the low-level languages.

- Implement C language-based extensions.

- Create multi-processes by using Spark or Hadoop

- Utilise Cython, Numba, and PyPy to speed up your Python code or write it in C and expose it in Python like NumPy

Which IDEs Do People Use?

- Spyder, PyCharm. Additionally various notebooks are used e.g. Jupyter

What Are The Top Python Frameworks And Packages?

- There are a large number of must-use packages:

PyUnit (unit testing), PyDoc (documentation), SciPy (algebra and numerical), Pandas (data management), Sci-Kit learn (ML and data science), Tensorflow (AI), Numpy (array and numerical), BeautifulSoap (web pages scrapping), Flask (microframework), Pyramid (enterprise applications), Django (UI MVVM), urllib (web pages scraping), Tkinter (GUI), mock (mocking library), PyChecker(bug detector), Pylint (module code analysis)

How To Host Python Packages?

- For Unix: Make script file mode Executable and the first line begin with:

#(#!/my account/local/bin/python)

2. You can use command-line tool and execute it

3. Use PyPRI or PyPI server

Can Python and R be combined?

- A large number of rich statistical libraries have been written in R

- One can execute R code within Python by using Rpy2 python package or by using a beaker notebook or IR kernel within Jupyter.

Is there a way to catch errors before running Python?

- We can use PyChecker and PyLink to catch errors before running the code.

Summary

This article outlined the most important 25 concepts of Python in a short, relevant and focused manner. I genuinely hope it has helped someone get a better understanding of Python.

I believe I have concentrated on the must-know topics that are absolutely required to be understood. This knowledge is sufficient to write your own python packages in the future or using existing Python packages.

Rest, just practice as much as possible and you can implement your own library in Python because this article contains all the knowledge you need.